Handicraft as a source

Before there was any printing technology, books and other writings were copied piece by piece by hand for their reproduction. Books literally consisted of a collection of manuscripts. An edition usually consisted of no more than a few dozen to a maximum of hundreds of copies. Many books from antiquity and the Middle Ages are therefore lost forever when the last copy disappears. This only increased their rarity over time.

The creator of art paper

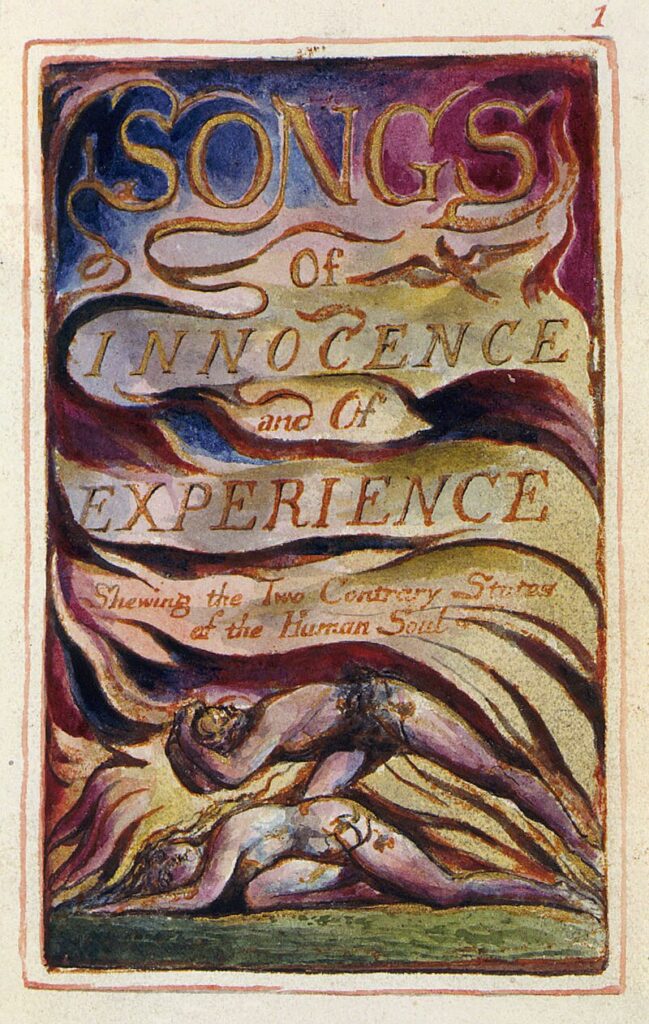

Artists were soon involved in the production of books in Europe in the early Middle Ages. Good examples of this are the Book of Kells or the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry. Then we usually speak of books that were illustrated by artists, based on stories, subjects and/or texts by others. The artist’s book phenomenon is attributed to the British poet and artist William Blake (1757–1827). His books were illustrated, colored and bound by his wife Catherine and Blake themselves and written and published independently. Striking and compared to other books, the illustrations flowed through the handwritten texts to form a coherent whole. This interwoven process of text, image and form was a new element in book art. And to this day they form the basic ingredients of artists’ books.

The influence of individual expression, of both the designer and the artist, was clearly visible in the publications of William Morris (1834-1896). Due to his faithfulness to nature and attention to the materials and methods used, his books were a second benchmark in the development of artists’ books. Morris was also the founder of the renowned Arts and Crafts movement in Great Britain. And in the 20th century, the Avant-garde artists in particular produced various books as an autonomous part of their artistic oeuvre. In addition to their own work, they also published various creative pamphlets, posters and manifestos. It was also a way for them to avoid the traditional gallery system, or to propagate (revolutionary) ideas. But certainly also to generate direct income from this and reach audiences who usually do not visit an art gallery. Artists who became prominent in this way are: the Italian futurist Filippo Marinetti (1876–1944), the Russian futurists Aleksei Kroetsjonych (1886–1968), Vladimir Tatlin (1885–1953) and Olga Rozanova (1886–1918), but also El Lissitsky (1890-1941), Kurt Schwitters (1887-1948), the Bauhaus movement. In the Netherlands, Theo van Doesburg (1883-1931) and the art movement De Stijl were examples of this.

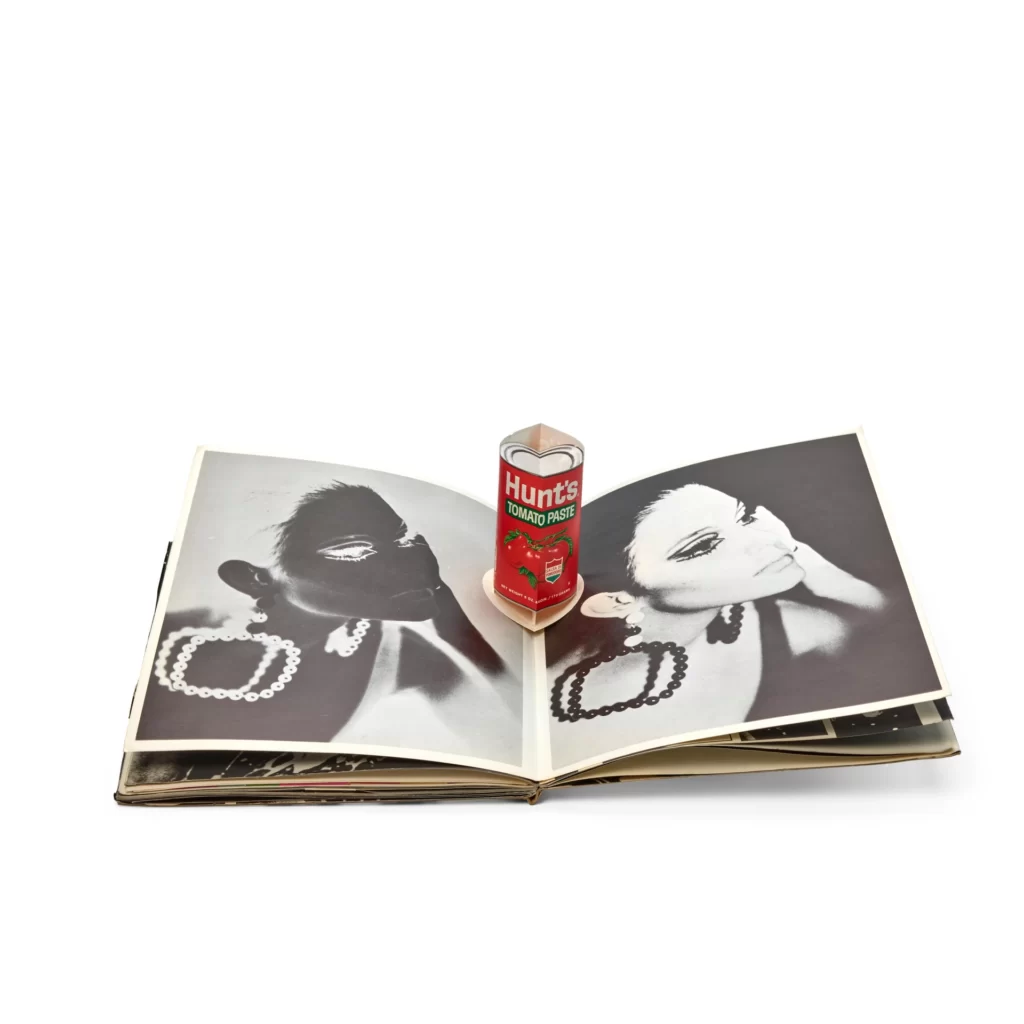

Later, in the 1950s and 1960s, conceptual works of art were sometimes regarded as the first real artist’s books. This was especially the case with some works (books) by the American artists Ed Ruscha (1937) and Andy Warhol (1928–1987), or the Swiss-German artist Dieter Roth (1930–1998). This followed a period in which artists from various disciplines began to experiment with the book as a medium. They no longer regard the book as a source of substantive information, an object of transmission. But position it as the artistic means of expression itself.

For his ‘Index Book’, Warhol made inventive use of the popular children’s book. As you turn the pages, all kinds of fantastic beasts and buildings jump out of the pages. The content is playful and humorous with: magazine-like images of famous and lesser-known people, a plane, a hot air balloon to inflate, a gramophone record and more surprises. The book is a mixture of convention and experiment.

In the meantime, the artist’s book has also increased in status in the Netherlands and forms its own collection area within the visual arts. The young art historian Frans Haks, later a controversial director of the Groninger Museum, was commissioned by the Art History Institute (KHI) of the University of Utrecht to create a collection of artists’ books. The current collection is now a valuable source of artistic and art historical information about artists from the 1960s. Within the visual arts, the artist’s book has become a genre that emerged strongly at the end of the last century. They are works of art that can take various forms, such as: scrolls, harmonica books, pop-up books, etc. But they somehow remain recognizable as a book. There are artists’ books that are produced in editions; the multiples. Of still others, only one copy exists; the unique.

The Belgian artist Begga Martens described this phenomenon:

An artist’s book is an experience for body and mind. In contrast to other books, the sensation of discovery, the experience of an artist’s book is much more intense, almost a sacred event. The act itself, picking up and studying the cover, full of impatience that lies behind it. This is not a book that you will find in every library or bookstore, no, this is a unique art object! No, this is a one-on-one relationship, between you and the book, yes, between you and its creator.